Not anti-dam, but pro-people and pro-environment

- Aug 3, 2022

- 11 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2024

ACTIVIST SPEAK

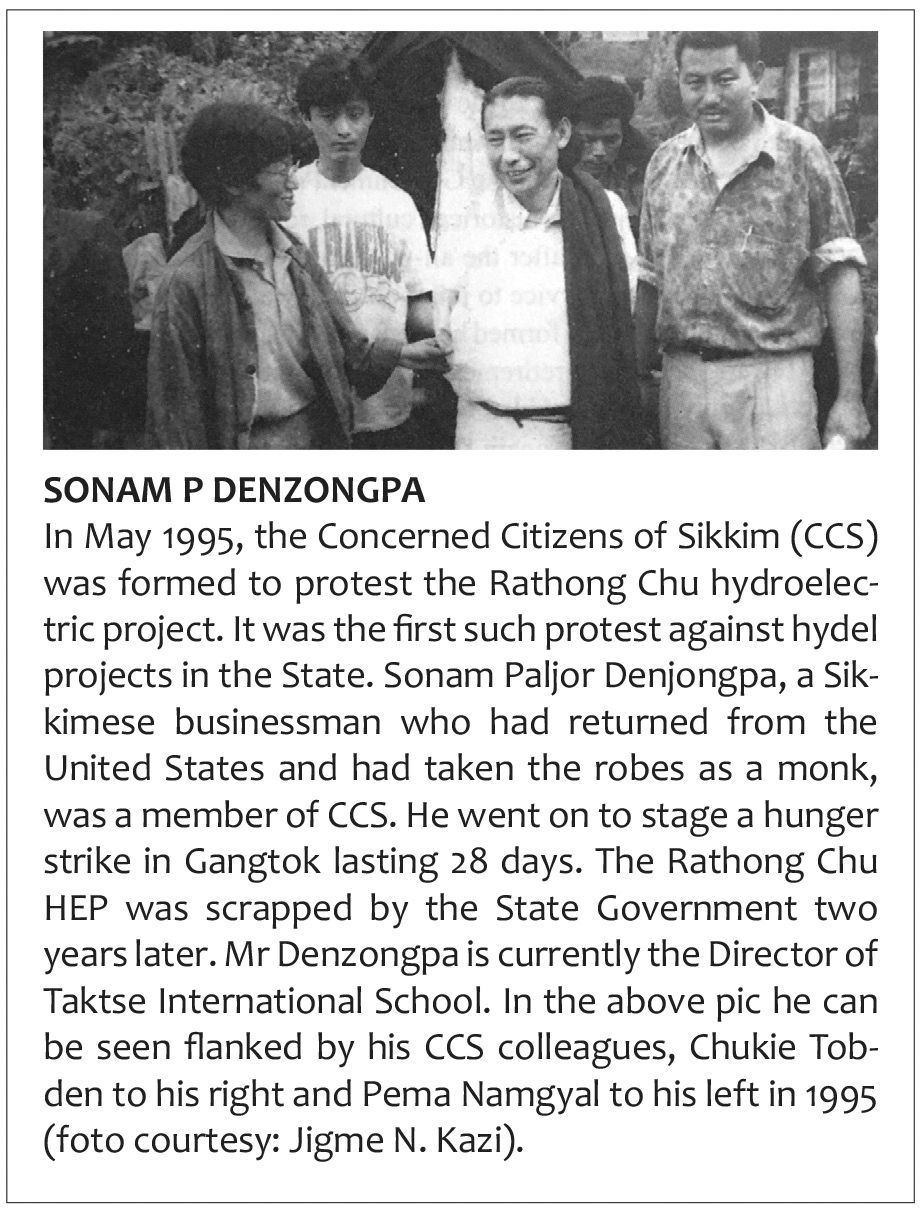

The first protest against hydel projects in Sikkim was launched in 1995 when

Sonam Paljor Denzongpa sat on a hunger strike for 28 days demanding the

scrapping of the Rathong Chu hydel project in West Sikkim. Twelve years

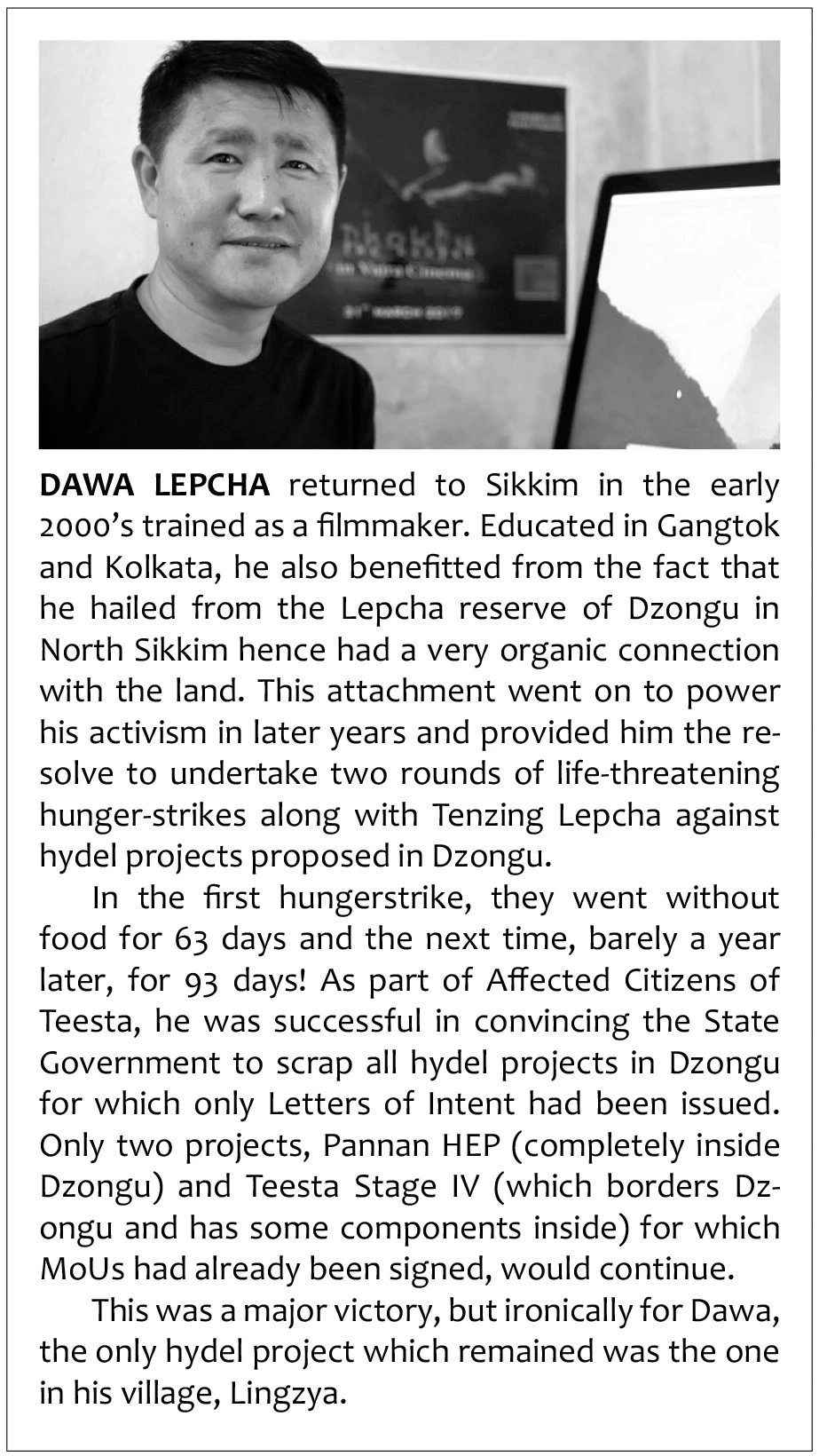

later, Dawa Lepcha along with Tenzing Lepcha sat on a 63-day hunger strike

also demanding the scrapping of hydel projects, but this time in North Sikkim.

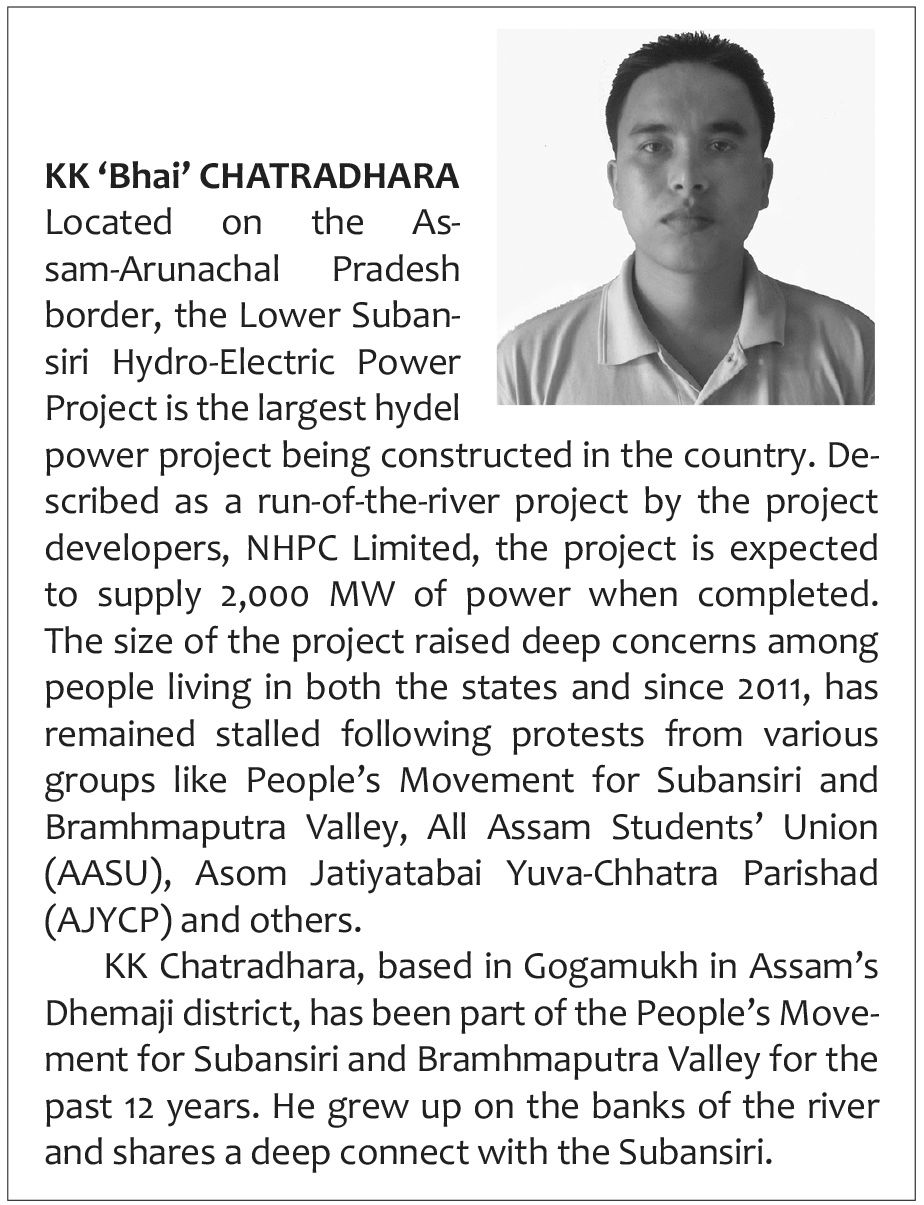

Around the same time in Assam, KK Chatradhara was also involved in protests

against the Lower Subansiri hydel project, the largest project in the country.

SummitTimes spoke to the three activists, posing them the same set of

questions in trying to get an understanding of what convinced them to risk so

much for causes which, despite the universal impact, attract the passions of

so few. Their activism and their sacrifices are well documented, here we try

and delve into their convictions, faith and drive.

[Sikkim monks, with Karma P Denzongpa in white bakhu in the middle, rallying in Gangtok on 09 July, 1995, against the Rathong Chu hydel. Foto courtesy: Jigme N Kazi]

Q. None of you had any overt political or activist engagements until you got

involved in your respective movements. What brought about this change?

What convinced you to get involved in direct action?

DAWA LEPCHA: I had just finished my training in filmmaking and had come back

home. I knew what was happening (with regard to hydel projects) but I thought it

would just be one project (Teesta Stage V HEP). In 2002-03, however, I found out

that 40-42 projects were being planned and I thought that was not a good idea. I met

a few people who were involved with the Teesta-V protest.

There is always that point where you get that spark, you know. One day, I had just

met Pemzang Tenzing and was going back to my village. I got off the vehicle and

started walking home. It was evening time, the sound of crickets was all around and I

was walking thinking about the hydel projects and all that. So as I was mulling over

all these things, I got a strong feeling that I cannot let this happen to my place, I am

not going to allow that. I was young, in my early 30s. That's when I made up mind I

think, to do something about it.

SONAM P DENZONGPA: We were at Pemyangtse Monastery for a wang ceremony

sometime in 1994. It was the Dorje Lopen, the Abbot, of the Pemayangtse

Monastery who said that these projects (Rathong Chu HEP) will destroy the sanctity

of the place. He was discussing plans on how the project could be stopped with

some other monks but they could not figure out how to go about it.

We talked to him and he said maybe it's our generation that will have to do

something about it. We discussed it amongst ourselves but we'd never done

something like this before.

The next day the Abbot passed away.

Then I felt like it had fallen upon me to do something about it. He had passed the ball

to us in a way.

KK ‘Bhai’ CHATRADHARA: People of Subansiri valley, even from Assam, were

happy to say “Subansiri project is coming and will brighten our future”, long back

during the 1990s to 2000. People demanded the project many times and it is even

enlisted in Assam Accord of 1985. So, I was born and brought up in an environment

where large dams were considered a good thing. At the same time, nature and our

culture got me closely involved with the river.

When the construction started, it was disheartening to see the destruction of the

beautiful landscape. I, Monoj and Binay started discussing about what development

really means, what actually are large dams? That was 17 years ago. That was when

I felt the need to get involved and build the movement. A paralysed Subansiri is

painful to imagine, not acceptable at all.

From your experience, what are some of the biggest challenges facing

environmental activists on ground?

DAWA: The biggest challenges are the lack of awareness among the masses and the

well-oiled greed campaign by the vested interests.

Talking about environment here is difficult. I don’t believe in all these programmes

held on environment, you know. They are all superficial. Actual work is never done.

People haven't really understood the concept of environment. For instance, if you

talk about saving trees in the villages, they will say 'there are enough trees here'.

When you talk about the harm such projects will bring about in the future, it is difficult

to convince people because we don’t have anything to show.

Maybe we were also not well equipped at that time, we could have found other ways

to do it. But then, convincing people is very difficult. You talk about environment, that

doesn’t work. You talk about social impacts, we don’t have anything to prove that.

You talk about culture and people think that is not something that can be affected.

SONAM: We didn’t know how to mobilize people. We relied more on the spirits and

prayers. There were a section of people who really believed in it. We also believed

that it’s in the mind. We weren't doing anything negative but we didn’t know how to

get things out and mobilize.

CHATRADHARA: Environmental activists have been defined as a “Response to

some type of threat to a person’s environment, their family or an area or place that

they love” (chase, 1999). Environmental activists usually emerge from the grassroots

and the shortfall of organic leaders on the ground is one of the biggest challenges in

current times. Also, it is easier to change the mindset of people who are anti

environmental groups but are not well informed. Those who know the costs of

harming the environment and yet oppose environmental groups, changing how they

think is a challenge.

How easy or difficult is it to gather information on hydel projects to build

arguments against it?

DAWA: Gathering information is not that difficult. By the time our movement came

about, the RTI Act had come in and the companies were also forthcoming. I think the

difficult part is the actual finances involved; who, where, how. Who really benefits

after the peanuts have been handed out.

Having said that, I have reservation about building arguments…it never ends. The

back and forth of it, often ending nowhere.

SONAM: It was interesting… things just fell into place. There was a young guy,

he is in Delhi now. So, he appeared and he was an environmentalist. He

said he wanted to help. Then people said that we have to go to court. So he went

and found a Supreme Court lawyer, Rajeev Dhawan, who just volunteered to help

us. And things started to fall into place. The government would do some kind of

video against our argument and they would not be able to release it…they would

plan fancy books about how good the hydel projects would be and somehow the

books just couldn’t get printed.

I think there were some people within the establishment also who felt that this is

really not right. There was land that didn’t exist, which on paper they claimed existed.

There were officers in the establishment who really helped us. I guess at that time

you couldn’t get such papers out and they just helped us get it.

CHATRADHARA: Up to a level, it is not that difficult. Most powerful way is to gather

as much information in favour of the projects, so that one can counter them.

Identity, beliefs or faiths are often invoked more than the environmental costs

in building arguments against hydel projects. Do you think it is part of the plan

or is there any planning involved at all?

DAWA: Of course, these above points are the most important and things that touch

the sentiments of the people facing the direct onslaught of these developmental

programs. So obviously they come in play whether there is a plan or not. If the

masses were to understand the environmental argument, things won’t be that difficult

at all.

SONAM: Sense of sacred is not just religious; it is about those things that have been

here for millions of years. Those are sacred. So worship means to appreciate and

acknowledge that, accept that because of them we are here. When you destroy

them, you are destroying the future generations to come. You have to let them be.

You don’t have to do anything. You just have to let them be. Let the lakes be, let the

forests be, let the rocks be. There are spirits that live in the rock called 'tsen', there

are spirits in the trees called 'lha', there are spirits that live in the water called 'lu'. All

these things are like us. They live, they are born. We don’t see them now because

our senses have become crude. As you become emotionally cruder you lose access

to all these other beings. I, my, me is the focus.

We don’t even see other human beings, forget about other kinds of beings.

People think environmentalism has come from the West but it has been a part of our

tradition for thousands of years. Mt Khangchendzonga was not made by Buddha, it

predates everybody. That's been here. It';s our protecting deity. For thousands of

years the rivers have been flowing. The belief that this is a hidden land means that

whatever we do here affects the whole cosmos. We don’t realize that. This place is

very important and it is important to do positive things here.

Look at the weather patterns. There is no one cause. It is a cycle. When you pollute

the sky it passes on to the water and in water lives 'lu' and 'lu' really suffers from

pollution and then we get affected. It is all a cycle. But, it is a different way to look at

it.

The hydel projects would carry out studies that would sometimes suggest that there were certain probable negative impacts but then suddenly they would come up with another report saying that everything is fine. It is basically greed. I am not so extreme as to say shut down all hydel projects but the river has to run. It is like our bloodstream, it has to run in our body. If you live in the mountains you've got to let the river flow. If you dam all the rivers, every living thing in the river gets damaged. What are you doing? I don’t think that they can promise to produce such things. It's

all calculations from their point of view. I wonder what will happen after 10-15 years and what we have destroyed, how would we build it back? Once it's destroyed, it's really destroyed.

Reality is not out there, it is in our minds. Belief is part of the reality. When those beliefs are alive that is the reality. You can't say this is real and that isn't. You can't show calculations and say that is real. That’s also made up. They say once it appears in numbers, that’s real. How is it real? That’s not real. We are living here, this place belongs to us and we have to take care of it.

CHATRADHARA: Identity, beliefs and faiths can be part of the argument against

hydel projects, however, we also need to emphasise and link science with each of

these. The environmental and socio-economic costs should be highlighted more.

In the case of Subansiri, one of the demands was a downstream impact study from

the dam site to the confluence up to Brahmaputra by involving local experts.

What do you think of environmental activists taking an apolitical stand,

choosing to steer clear of any links with political parties or ideologies? Do you

think activism can or needs to be divorced from politics?

DAWA: After my experience and whatever environmental successes or failures

there have been around the world, it is not easy to have apolitical stand. One way or

the other politics will get in. Even when the activists try to keep the movement clean

of politics it is difficult. All these because there is the scrupulous opposite group hell

bent on having their vested interest implemented one way or the other. ACT was

projected as opposition party! Ground reality is very different. I think it all boils down

to ‘whether you want result or you want to plod on and on and on?!”

So, my analysis is something like this. Suppose there is a political party which is in

power and on the other side there are a few activists. When the activists' voices are

not heard, they have to look for support elsewhere. That's when the opposition

parties will try to come in. Even if the activists refuse their support, the ruling party

will accuse the activists of being hand in glove with the opposition. Then the ruling

party will activate its grass root level workers to lobby against the activists making it

all the more difficult for the latter to convince people.

SONAM: We try to stay away from politics, as in party politics. When it comes to

party politics, suppose one person comes to support you, because of that, another

guy is against you. And you are in a camp now. When (opposition) politicians came

to us, I just said look… this is for us, for the people, for the sacred land. Staying

away from politics means not falling under any camp to avoid getting used. But I

think it is political…in a way.

CHATRADHARA: Environmental activism is beyond political ideology or parties but

one can’t ignore the politics in activism as well. A meaningful distance from political

and religious activists helps to achieve the purpose of environmentalism. It seems

political activists put environmental issues in their agenda to take the chair for 5-10

yrs. As the present Prime Minister did in 2014 by saying that “I know citizens of

Arunachal Pradesh are against the large projects. I respect your sentiments. But

protecting the environment and using environmental technology, hydropower can

also be harnessed using smaller projects.” It was propaganda to win over the people

for the short run.

Environmental activism continues to struggle in garnering mass support and

wider public participation. What do you think is the reason behind the failure

of so many protests across the globe? Why is environmental activism limited

to the directly affected and how would you define 'stakeholders'?

DAWA: If you talk about environment, people don’t understand. So you’ve got to find

a strategy that works. Otherwise you are just 2-3 people shouting and nobody is

listening. In the case of Dzongu, whether you like it or not, most of the land being

taken for hydel projects belonged to Lepchas. So you can't help the movement

becoming about Lepchas.

And it also becomes a strategy when all else fails. You talk about impacts on fish

migration and they (project developers) will show you fish ladders. By the way, not

one dam has a fish ladder. If you talk about deforestation, they’ll say mass

plantations will be carried out.

As for the definition of stakeholders, it would comprise of the entire state and not

only the directly affected but I think awareness levels among the general public is

low.

SONAM: Sometimes I feel like we are not a nation anymore. It's Dzongu… its

religion. For instance our movement was about religion. There was incredible

opposition but there wasn’t any real mobilization either, mass mobilization that is. It's

Dzongu, it's Lepchas. There was no mass movement and that shows that the

connection was missing. We fail to understand that this is our land, no matter who

you are. Actually Guru Rinpoche had said people born here are my people, you take

care of this land. Somehow this unity has broken down into different communities.

Movements like these would be branded as Buddhist movement but we all share the

river. It's ours, for generations to come. But that was difficult to overcome.

The positive thing was that those who could not support us openly were not ready to

be manipulated by the political camps either. They did maybe feel like they weren't

directly affected by the dams but they did not allow political groups with vested

interests to push them against us either. So, it's unique.

CHATRADHARA: Romanticising environmental movements is one of the reasons

for their failure. Class structures amongst the environmentalists/ activists is also

adversely affecting movements as a whole. This happens to any form of movement.

The concept of development is imposed with colonial mindsets and this is deeply

rooted everywhere, so it is difficult to change the present form of developmental

attitude within a limited period. It is human behaviour to respond or react only when

you are hit and so is the case with environmental movements limiting activism to the

directly affected. But, Subansiri includes many other environmental movements so such limitations do not apply here. There is good support for the movements, only a few do not support

us.

Comments